How Are Football Clubs Governed, Incorporated & Acquired In South Africa?

08 December 2022

Governance

Football

Sports Business

Commercial / Contracts

Thursday, 08 December 2022 By Shane Wafer, Nicholas Flowers

South Africa is a country whose name is synonymous with football; and that existed long before the now-iconic Waka Waka. A cursory look at the country’s football history confirms as much. The “rainbow nation” is home to one of Africa’s oldest clubs[1] and the site of Africa’s first (and, to date, only) FIFA men’s World Cup[2]. Financially, they are no slouches either boasting the continent’s wealthiest league[3] and three of Africa’s wealthiest clubs[4].

Despite a strong financial position and with over 500k registered players at their disposal, South African clubs have surprisingly failed to achieve major success outside the country’s borders, at the continental level. In the CAF Champions League, Africa’s biggest club tournament, South African clubs have only managed to return two titles[5] since the inception of the tournament in 1964[6]. Tunisia and Egypt alone have returned as many as 23 titles between themselves; each having three different teams achieve success. There is no doubt South African football has yet to fully realise its true potential.

This article will examine the current system for regulation and governance of South African football clubs. Readers will learn the various requirements around the acquisition, operation, ownership and disposition of interests in a professional club team.

With reference to case studies, we will examine the recent trend within the industry to buy and sell football clubs within short periods of time, which we argue may potentially affect the long-term sustainability of South African football.

The article discusses the following:

- Setting The Scene: South African Football’s Structure

- The Incorporation Of Clubs: NSL Handbook & The Companies Act

- Going Pro: Purchasing Or Selling A Club In South Africa

- Lessons From Recent Transactions – Does The NSL Need To Enforce Stricter Sale Regulations For Top Clubs?

- Looking Ahead And Concluding Remarks

Setting The Scene: South African Football’s Structure

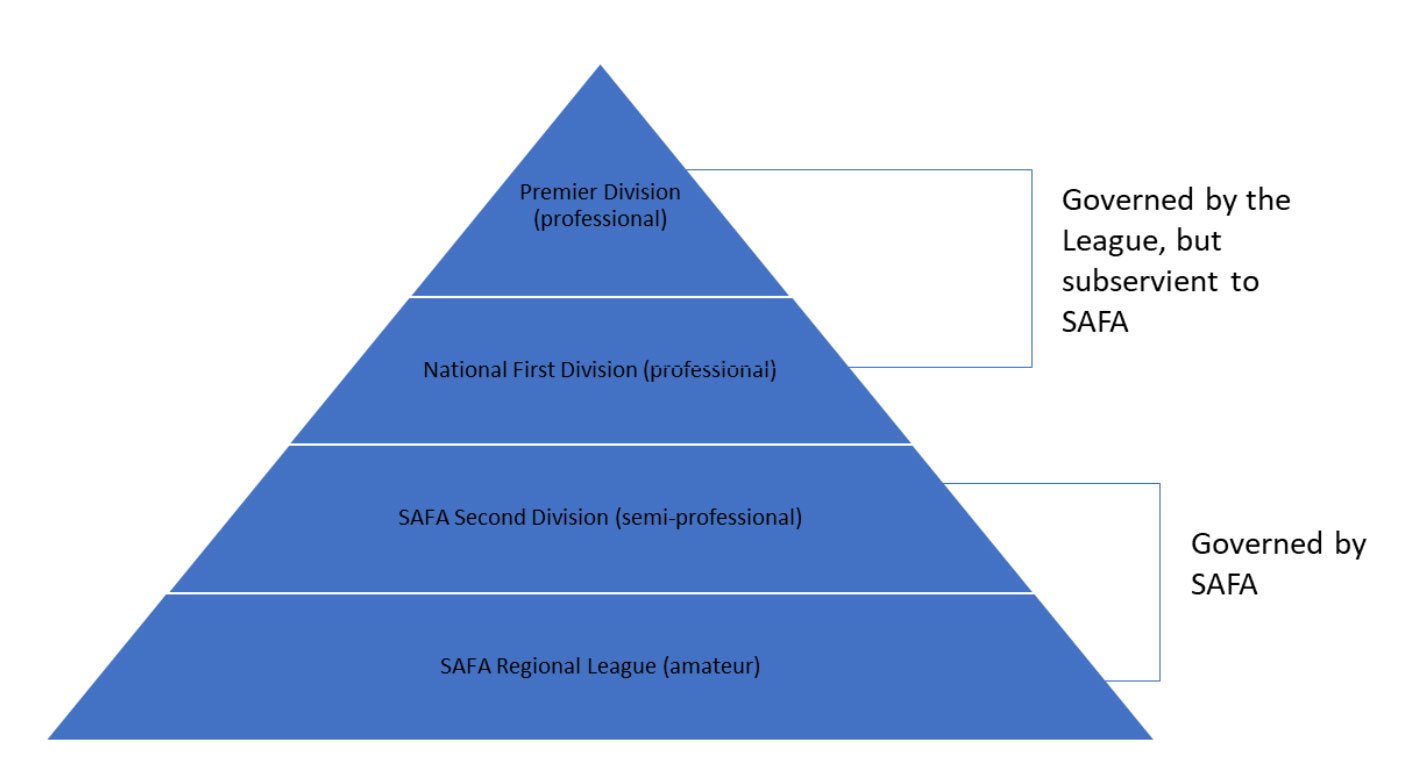

South African football is subjected to a “pyramid system of governance”[7]. At the apex, regulation of the sport in the country is vested in the South African Football Association (SAFA). SAFA is both a member of South Africa’s national Olympic committee and the Confédération Africaine de Football (CAF). By virtue of these positions, SAFA is empowered to oversee the development, promotion, and regulation of all football in South Africa, whether professional or amateur.

As part of the hierarchal structure of football globally, SAFA is also a Member Association of FIFA and thus subject to the global governing body’s overarching control and authority.

Presently, there are four major tiers for male football. The top two tiers in the male section are the Premier Division[8] and the National First Division[9]. These are the only professional tiers and are collectively governed by the National Soccer League (NSL). The NSL is a voluntary association “which conducts its affairs under the name and style of the Premier Soccer League (PSL[10])”[11] i.e. PSL is essentially the trading name of the NSL. The NSL is accorded status as Special Member of SAFA[12]. As a result, “the rights, powers and obligations of the [League] shall be as set out in [the SAFA Statutes] and in the NSL Handbook [] or any amendment thereof approved by SAFA”[13]. The NSL Handbook (Handbook) contains the League’s Constitution and a set of rules governing issues such as membership, the transfer and status of players, acquisition and ownership of a club and dispute resolution, amongst other things.

Through the Handbook, the League regulates all professional male football in South Africa “within the confines of the SAFA, CAF and FIFA Statutes”[14]. The remaining tiers are the SAFA Second Division[15], and SAFA Men’s Regional League[16], which are both administered by SAFA.

Women’s Football

Conversely, there are two tiers for female football. The top tier is the SAFA Women’s League[17]. This is the only professional female league in South Africa, formed in 2019 and known in 2022 as the “Hollywoodbets Super League”. The second tier is the Sasol Women’s League[18]. Both of these tiers are administered by SAFA.

Graphically, the structure of South African football looks as follows:

Figure 1: Hierarchal structure of male football in South Africa

Figure 2: Hierarchal structure of female football in South Africa

The Incorporation Of Clubs: NSL Handbook & The Companies Act

SAFA defines a club as “a Member of the leagues affiliated to a Member, Special Member or associate Member of SAFA”[19], whilst the NSL Handbook defines a club as “any football club registered with or affiliated to a federation, association, or body, recognised by FIFA”[20].

In order to have a thorough understanding of the football landscape in South Africa, it is practical to recognise the provisions of the Companies Act 71 of 2008 (Companies Act) as they relate to clubs. The most common form of incorporation for a professional football club in South Africa is a private company with limited liability[21]. Therefore, all clubs incorporated in this manner are subject to the provisions of the Companies Act.

This creates numerous obligations for owners, including financial reporting requirements, labour law considerations for employees (players), as well as the owners and directors’ general fiduciary responsibilities owed to the organisation.

Perhaps most importantly, Section 7 of the Companies Act, setting out the legislation’s purpose, establishes that companies, and thus clubs, must seek to “encourage transparency and high standards of corporate governance as appropriate, given the significant role of enterprises within the social and economic life of the nation”.

In deciding what form of entity to incorporate a club under, various factors need to be considered, for example[22]:

- The ease with which formation can be made;

- Whether the pursuit of profits is a driving factor in the venture;

- Regulatory requirements applicable to the various forms;

- Concerns around legal liability;

- Need for perpetual succession;

- Capital available to fund the entity; and

- Tax considerations.

After the form for incorporation is decided upon, a prospective club needs to engage in SAFA’s club licensing process. This includes the submission of various documents to satisfy certain enumerated criteria, including sporting capacities, infrastructure, personnel and administration, legal and financial.

Football clubs subject to the authority of both the NSL and SAFA are ultimately corporate entities and therefore, must ensure compliance with all national legislation regulating corporate entities.

Going Pro: Purchasing Or Selling A Club In South Africa

In assessing what the applicable regulatory requirements are for purchasing or selling a club, it is necessary to consider where it is situated within South Africa’s football landscape.[23]

Male Professional Clubs

The acquisition or disposition of an interest in a club competing under the NSL’s auspices is governed by Article 14 of the Handbook. This Article is broad and applies to the “controlling interest or shareholding in a Member Club or entity that controls a Member Club, or the right to participate in a particular division of the NSL, or its membership of the [NSL]”[24]. In order to ensure compliance with the Article, and, in turn, effectuate the sale, transfer or disposition of a direct or indirect interest in a club, two requirements must be met:

- First, compliance with Article 18bis of the FIFA Regulations on the Status and Transfer of Players (FIFA RSTP). This Article provides that: “No club shall enter into a contract which enables the counter club/counter clubs, and vice versa, or any third party to acquire the ability to influence in employment and transfer-related matters its independence, its policies or the performance of its teams”.

- Second, prior written approval must be obtained from the executive committee of the NSL (Executive Committee)[25]. This requirement exists even for “any transaction directly or indirectly having any of the effects referred to”[26] upon a shareholding interest in a club or its right to participate within the NSL. Such approval, therefore, would apply to minority stake sales as well as controlling interest acquisitions.

Article 14 further sets out that the Executive Committee “will not unreasonably withhold or delay approval”[27] of an application which satisfies all the requirements imposed by the Executive Committee. These requirements may include, but are not limited to:[28]

- The prior written approval of SAFA must be obtained should the sale, transfer or disposition of a member club or controlling interest or shareholding be to a foreign person or entity or any ‘Third Party’ as defined in the FIFA RSTP;

- The written and signed agreement giving effect to this transaction must be furnished to and approved by the Executive Committee;

- All employment contracts concluded by the member club will be honoured notwithstanding any pending transaction; and

- The acquirer must satisfy the Executive Committee of the future financial stability and sustainability[29] of the member club.

Restrictions are also placed upon who may file an application under Article 14 with the Executive Committee. These include a prior-interest restriction, where the applicant “held an interest or shareholding in another club falling under the jurisdiction of the League in the 12 (twelve) month period preceding the transaction”[30]. Practically, this can be illustrated as follows: Owner A owns a football club in the National First Division, which is then relegated. Immediately following the conclusion of the season, Owner A wants to purchase an interest in a Premier Division team. Because the NSL’s jurisdiction encompasses both the Premier Division and National First Division, Owner A would need to have sold their interest and then waited 12 (twelve) months before attempting to purchase an interest in another club within either division of the NSL.

A successful application will almost always be subject to certain conditions concerning the “defining elements” of a member club, which must remain unchanged. Examples of what comprise these elements are:[31]

- City or town in which the home venue of the member club is situated;

- Colours of the member club;

- Name of the member club; and

- Registered or unregistered trademarks, logo or any depiction on a team outfit.

An applicant may be relieved of these conditions “where express and additional written approval is granted by the Executive Committee”[32].

Non-NSL Clubs

SAFA is responsible for all other clubs that fall outside the authority of the NSL. As such, it is necessary to consult the SAFA Statutes, and various rules and regulations promulgated thereunder.

Unlike the NSL Handbook, the SAFA Statutes do not contain a clear process for dealing with the purchase and sale of a team. Instead, a patchwork approach is necessary to identify the principles and procedure guiding the process within the various SAFA rules and regulations.

The SAFA Women’s League, Sasol Women’s League, SAFA Second Division and SAFA Men’s Regional League (SAFA Leagues) each contain their own competition-specific rules. None of these rules contain provisions for dealing with the acquisition or disposition of an interest in a member club.

However, these rules are all made subject to the SAFA Uniform Competition Rules (Uniform Rules). The Uniform Rules are promulgated by the Organising Committee for SAFA Competitions (Competitions Committee), who are empowered by Article 39 of the SAFA Statutes to ”organise and monitor the competitions of SAFA in compliance with the provisions of the Statutes and the regulations applicable to SAFA competitions”[33].

Under the Uniform Rules, “No team [is] allowed to sell its franchise and relocate its home base unless such a transaction is sanctioned by the SAFA National Executive Committee [(NEC)] on the recommendation of the Competitions Committee, which permission will not be unreasonably withheld”[34]. Specifically highlighted is that a team’s “entitlement to participate in a league championship will depend principally on sporting merit”[35].

In assessing a proposed sale, the NEC and Competitions Committee will apply an impact-analysis approach, which considers whether the sale of a franchise:[36]

- Is to the detriment of a league championship;

- Results in a changing of headquarters;

- Results in a changing of a team’s name;

- Results in a changing of a team’s stakeholders; and

- Is to the detriment of the integrity of sports competition.

A sale which satisfies the criteria of (i), (v) and any of (ii)-(iv) above will be prohibited.

Absent a detrimental impact to the league championship or sports competition, “No team will be allowed to change its name without the prior approval of SAFA, on the recommendation of the Competitions Committee, which will not be unreasonably withheld”[37]. Additionally, in the event of a team being sold and relocating, it will suffer relegation, “except where the Competitions Committee decides otherwise after considering a properly motivated application to that effect.”[38]

All newly purchased franchises must be affiliated with the SAFA league football associations in which their home bases are situated. A team failing to observe this provision, will be guilty of misconduct and liable to any sanction in terms of the Uniform Rules, SAFA Statutes, or SAFA disciplinary code[39].

Applicable National Legislation

When a club is sold in South Africa, the transaction will occur as a transfer of a business as a ‘going concern’, i.e., the operational business of the club that is transferred remains materially the same but merely sits in new hands (ownership). Sale of business agreements, incorporating a transfer of securities[40] will always be subject to the Companies Act and therefore will be bound by strict governance and financial reporting requirements.

Other legislative provisions, such as Section 197 of the Labour Relations Act 66 of 1995 (LRA), as amended, regulates the effects of a transfer of a business on the employment contracts of affected employees (players) and, in particular, provides for the automatic transfer of employment contracts from the transferring employer (old employer) to the acquiring employer (new employer). The LRA aims to prevent situations whereby the sale of a football club results in large portions of the roster having their contracts terminated by a new employer, who may want their ‘own’ players. In fact, the LRA provides multiple layers of protection to employees (players) where there is a transfer of a business (club), that may result in material changes to certain agreed working conditions. Failure to consider the fundamental terms of the employee’s (prior) contract as they relate to location or salary, may result in a claim for automatically unfair dismissal.[41]

Both the NSL Handbook and domestic legislation play an integral role in any acquisition or disposition of a professional club and owners must ensure a comprehensive understanding of the various implications associated with acquiring and/or disposing of a professional football club.

Lessons From Recent Transactions – Does The NSL Need To Enforce Stricter Sale Regulations For Top Clubs?

Bidvest Wits (Wits) was founded in 1921 by the Wits University’s students representatives council. The team was based at the university, which is one of South Africa’s most storied tertiary institutions. Wits has long been a well-known and iconic South African football club. In 2020, one year short of their centenary, Wits lost its storied legacy as a club.

41 years after first achieving promotion to the top tier of South African football, Wits’ personal zenith would be achieved when they won the league title in 2016.

Only three seasons after winning the premier domestic league in South Africa, Wits, owned by JSE-listed Bidvest Group in partnership with the University of the Witwatersrand, sold its Premier Division status to Second Division team Tshakhuma Tsha Madzivhandila FC (TTM)[42], thereby resulting in a merger between the two clubs. The team was renamed and relocated, with a fire sale of its players, many of whom comprised that championship squad. The club previously owned by Wits (now TTM) sported a new name, a new logo, a new brand and ultimately a completely new identity. Despite the plethora of ‘defining elements’ that were changed, the PSL Executive Committee authorised the transaction.

Only seven months later, after a first season that saw them languishing at the bottom of the table, TTM sold its status to a company called Protoscape 202 CC, with the team being renamed the Marumo Gallants. The initial organisation known as TTM then purchased the National First Division status of Royal AM Football Club, relocated the club and promptly renamed them TTM.

In 2021, the previous owners of Wits re-entered the South African football landscape after they purchased the status of Baberwa FC in the third division, renaming the club to Wits FC. Other teams to have changed their name and location in recent times include Highlands Park and Bloemfontein Celtic. AmaZulu changed ownership in 2020 but their “defining elements” (and their name) remained in place.

Could all of this manoeuvring of clubs and identities have a negative effective on the greater football landscape in South Africa? SAFA has intimated that it intends to “clamp down” on the process whereby the sale of a team results in historic franchises from potentially having their identity scuppered[43]. But is that enough, particularly when all the purchase and sale rules do not appear to go far enough?

Top-flight football in South Africa is at risk of becoming “pay to play”. Teams do not need to fight their way up the footballing pyramid when they can simply purchase the status of a financially stricken top-flight team. The depth of an owner’s pockets therefore becomes more important than the ability of a team. The cooling-off period of one year under the Handbook is also not long enough in order to prevent owners from chopping and changing on a whim. This discourages the practice of developing and maintaining a sound business plan which targets long-term growth for a club.

Identity matters, and constantly changing the foundations of a club will inevitably invite issues at all levels of the organisation.

When it comes to assessing the potential interests of an investor in acquiring a club, there appears to be no “fit and proper person” test by which an individual (or one controlling a purchasing entity) is properly vetted[44]. If these important decision makers are not being adequately verified, it stands to reason that they may potentially jeopardise a league’s leadership and sustainability.

Lost amongst all of this is perhaps the most important stakeholders: the fans. Administrative rules and regulations often have public impact assessments as part of their enactment and amendment process. Surely, sports now occupy the position of being a quasi-public good, such that its impact on stakeholders be mandated for any relocation?

South Africa’s footballing rules and regulations do not contain territorial restrictions, like those seen in Major League Soccer (MLS). The result is that teams may relocate and eat into another’s market. High-density areas may be left with no professional teams to support and teams that have existed since time immemorial may suddenly be gone overnight, renamed to whatever the highest-paying naming rights sponsor is willing to pay. Although, the viability of such a system needs to be understood in the context of MLS having no promotion or relegation; with the MLS currently having 28 professional clubs. By contrast, South Africa has in excess of 32, not including possible compositional alterations due to promotion and relegation. Geographic restrictions across a country which is a lot smaller than the United States of America would be impractical. While territorial rights like those seen in MLS may not be feasible, any possible sales should look at whether it will result in a given geographic area being deprived of any professional club, or one whose historical significance weighs against relocation.

The existing framework (the “Framework”) provides some laudable objectives, but it is deficient insofar as it fails to really position football first.

Looking Ahead And Concluding Remarks

South Africa is a football-mad nation with an unyielding appetite for the sport. This has resulted in the country indelibly etching its name amongst the history of African football. Despite this, continental success has always seemed to elude South African professional clubs, notwithstanding the evident wealth which some teams and the League possess. European examples of the nouveau rich show how a purchase by a wealthy owner may not always translate to tangible success on the field.

Both SAFA and the League are responsible for the governance, regulation and administration of professional female and male football in South Africa, respectively. The League is given autonomy to act and run its affairs, to the extent that none of its conduct, rules, or regulations run contrary to the SAFA Statutes. Both bodies contain their own rules governing the purchase and acquisition of professional clubs. For SAFA, the Uniform Rules is the governing document, which considers the detrimental impact which a sale may have on either the league or sporting competition. The Handbook contains similar provisions, along with demonstrated compliance with Article 18bis. Together, the Framework emphasises that, absent approval, definitional elements of clubs cannot be changed following a sale.

However, recent examples have shown the deleterious impact which the sales of professional football clubs in South Africa can have. Historic franchises seemingly disappear overnight, robbing fans, and the leagues themselves, of clubs intertwined with the history of sports in South Africa. Furthermore, the emergence of “pay to play” models threatens to curtail any league attempts to ensure parity, stability, and sound governance principles.

It is submitted that the Framework is deficient in that solvency/liquidity considerations are not given sufficient weighting, while little exists in the way of preventing conflicts of interest. Furthermore, a short cooling-off period for serial club owners coupled with absence of any assessment made of a purchasing individual’s capacity, does little to temper concerns around the potential for corruption at the highest level of South African football.

South Africa presents an interesting case study in identifying how things can be greatly improved, in order to drive meaningful change. To paraphrase Shakira, “[It’s] time for [South Africa]”.

As written for LawinSport: https://www.lawinsport.com/topics/sports/item/how-are-football-clubs-governed-incorporated-acquired-in-south-africa#references

REFERENCES

[1] J Cook, ‘Pietermaritzburg’s Savages FC celebrates 140 years’, Citizen [website], published 1 October 2022, https://www.citizen.co.za/witness/sport/pietermaritzburgs-savages-fc-celebrates-140-years/ (last viewed 31 October 2022).

[2] Agence France-Presse (AFP), ‘South Africa in bid to host 2027 Women's World Cup’, IOL (website), published 20 September 2022, https://www.iol.co.za/sport/soccer/south-africa-in-bid-to-host-2027-womens-world-cup-bfd1d3a5-d168-4d99-ad3a-f72e18c1a43b (last viewed 31 October 2022).

[3] Sospeter Itolondo, ‘Which is the richest football club in Africa in 2022, what is their value and source of income?’, Sports Brief [website], published 12 March 2022, income/#:~:text=The%20richest%20league%20is%20the,most%20supported%20throughout%20the%20continent. (last viewed 31 October 2022).

[4] Statista, ‘Most valuable football clubs in Africa as of the 2021/2022 season, by market value’, Statista [website], published June 2022, https://www.statista.com/statistics/1231531/most-valuable-football-clubs-in-africa/ (last viewed 31 October 2022).

[5] Orlando Pirates in 1996 and Mamelodi Sundowns in 2016.

[6] Originally created in 1964 as the African Cup of Champions Club. RSSF (website) published 18 January 2018, https://www.rsssf.org/tablesa/afcup64.html#cc (last viewed 12 November 2022)

[7] André Oliveira, ‘The “Pyramid System”’, Lex Sportiva [web blog], published 22 March 2019, https://lexsportiva.blog/2019/03/22/the-pyramid-system/ (last viewed 31 October 2022).

[8] Currently known as the ‘DStv Premiership’.

[9] Currently known as the ‘Motsepe Foundation Championship’.

[10] Used interchangeably herein with NSL.

[11] NSL, ‘The National Soccer League Handbook’, PSL [PDF], as adopted and approved on 11 July 2022, https://images.supersport.com/content/NSL-Handbook-as-Adopted-and-Approved-on-11July2022.pdf (last viewed 31 October 2022).

[12] SAFA Statutes, as amended on 26 March 2022, s. 10.3. This status expressly confers upon the NSL all the rights, powers and obligations of other ordinary members of SAFA. The NSL is accorded “Special” status by virtue of the fact that it has a direct interest in SAFA matters, but the nature and form of the NSL is not similar to those of other members, i.e., regional football associations defined by municipal areas or associations formed to represent a specific aspect of football like university sport. Because of this, the NSL is the only Special Member of SAFA.

[13] SAFA Statutes, as amended on 26 March 2022, s. 10.3.2.

[14] NSL Handbook, as adopted and approved on 11 July 2022, s. 7.1.2.

[15] Currently known as the ‘ABC Motsepe League’.

[16] Currently known as the ‘South African Breweries Regional League’.

[17] Currently known as the ‘Hollywoodbets Super League’.

[18] Sasol, ‘About Sasol League’, Sasol [website], 2018, https://www.sasolinsport.co.za/league/about-sasol-league/ (last viewed 31 October 2022).

[19] SAFA Statutes, as amended on 26 March 2022, Definitions.

[20] NSL Handbook, as adopted and approved on 11 July 2022, s. 1.10.

[21] Other forms include non-profit organisations (like voluntary associations), public-benefit organisations, partnerships and public companies, amongst other forms.

[22] Please note that this list is non-exhaustive, and every situation would need to be analysed on a case-by-case basis, which may reveal additional factors.

[23] As illustrated in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

[24] NSL Handbook, as adopted and approved on 11 July 2022, s. 14.1.

[25] NSL Handbook, as adopted and approved on 11 July 2022, s. 14.2.

[26] NSL Handbook, as adopted and approved on 11 July 2022, s. 14.2.

[27] NSL Handbook, as adopted and approved on 11 July 2022, s. 14.3.

[28] NSL Handbook, as adopted and approved on 11 July 2022, s. 14.3.1-14.3.4.

[29] This financial review is similar to the approaches taken in Mexico and Spain.

[30] NSL Handbook, as adopted and approved on 11 July 2022, s. 14.4.

[31] NSL Handbook, as adopted and approved on 11 July 2022, ss. 14.5.1-14.5.4.

[32] NSL Handbook, as adopted and approved on 11 July 2022, s. 14.5.

[33] SAFA Statutes, as amended on 26 March 2022, s. 39.1.

[34] Uniform Rules, as approved on 25 June 2016, s. 4.3.1.

[35] Uniform Rules, as approved on 25 June 2016, s. 4.3.1.

[36] Uniform Rules, as approved on 25 June 2016, s. 4.3.1.

[37] Uniform Rules, as approved on 25 June 2016, s. 4.3.3.

[38] Uniform Rules, as approved on 25 June 2016, s. 4.3.2.

[39] Uniform Rules, as approved on 25 June 2016, ss. 4.4.1-4.4.2.

[40] See Definition of “securities”, Companies Act 71 of 2008, as amended.

[41] See Section 197(3)(a) of the LRA.

[42] “TTM FC are based in the Limpopo province and previously purchased their current GladAfrica Championship status from Milano United FC in July 2017.” News 24 - ‘ Bidvest Wits' PSL status bought by TTM FC, expected to move to Thohoyandou’ News24 [website] 2020 https://www.news24.com/sport/Soccer/PSL/just-in-bidvest-wits-psl-status-sold-to-ttm-fc-20200613 (last accessed 5 December 2022)

[43] Delmain Faver, ‘SAFA take harsh decision on club sales’, Soccer Laduma [website], published 21 January 2022, https://www.snl24.com/soccerladuma/local/safa-take-harsh-decision-on-club-sales-20220121 (last viewed 31 October 2022).

[44] Sigwili Gumede, ‘My Take | Safa and the PSL must tighten club ownership change processes’, City Press [website], published 21 January 2022, https://www.news24.com/citypress/sport/my-take-safa-and-the-psl-must-tighten-club-ownership-change-processes-20210129 (last viewed 31 October 2022).